Scientists have been researching how hurricanes contribute to the spread of invasive marine species including the lionfish. Now local fisherman and community activist Captain John Howes, believes the Caribbean-wide lionfish invasion coincides with the invasion of the Sargassum Seaweed.

2018 is expected to be another record year for Sargassum Seaweed Invasion, according to national weather centres and officials at the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (CRFM). The influx has already closed a resort on Antigua and forced regional governments to inject hundreds of thousands in clean up. Howes believes Caribbean governments have another urgent reason to deal with the seaweed and that is due to a possible link with the lionfish which has become the major predator of fish in the region, causing massive reductions in the fish population and loss to fishermen.

In 2015, Science Daily reported that “researchers at Nova Southeastern University’s (NSU) Oceanographic Center discovered that storms … have a dramatic effect on ocean currents, which helps the spread of marine invasive species throughout a region. More specifically, NSU researchers looked at the distribution of lionfish in the Florida Straits.

“The researchers found that as a hurricane passes, the flow of water shifts from a strong, northern flow to a strong, eastern flow. It’s these changes in flow direction and speed that likely carry lionfish larvae and eggs from Florida to the Bahamas and can explain how lionfish were able to cross the Gulf Stream so soon after their introduction to South Florida waters,” noted the article.

Lionfish are also very sedentary. They take the path of least resistance and effort. In a recent tagging study of lionfish documented here, lionfish were proven to have ‘high site fidelity’, meaning that many of the tagged lionfish were recaptured in the exact same spot, and some were captured seven months later 200 feet away.

While he acknowledges the role of storms in the movement of the fish, Captain Howes believes these lazy fish could not have ended up in Barbados before they were discovered in Montserrat without additional help. He believes the rapid spread of the lionfish out from the Bahamas is linked to the emergence of the Sargussum Seaweed, which since 2011 has become a recurring trial for many Caribbean islands.

Howes became interested in learning how these fish were expanding their territory so rapidly while battling the strong currents of the gulf stream. The lionfish were first discovered near Florida and The Bahamas, where the story (now thought to be a legend), was that they had been accidentally released during Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

By early 2010, he said, two months prior to any Lionfish sighting, it was reported in all the islands from the BVI/USVI to Guadeloupe/Dominica, that Sargassum seaweed was floating in the ocean and on the beaches.

“The mass was so large that it looked like major oil slicks. Then just two short months later, lionfish were everywhere. I became so amazed at their speedy influx into our waters, I began researching online and communicating with fishers from around this region,” he said.

In September of 2012, Howes travelled to Guadeloupe to attend a meeting of all the lead fishers of Guadeloupe, who were concerned about the rapid lionfish invasion. There, French marine biologists were sharing how the invasive lionfish were taking over the reefs and fishing grounds.

While his own efforts to find recorded scientific research that the two things were linked have been fruitless, Howes is steadfast the lionfish invasion is directly connected to the dispersal of the fish and its eggs via the Sargassum Seaweed rafts across the Caribbean.

“My friend who is a commercial fisherman in Guadeloupe, was about 30 plus miles out into the Atlantic Ocean, trolling for dolphin/mahi mahi. As he was passing a Sargassum weed raft, he saw a white five gallon plastic bucket floating, so he picked it up and on doing this discovered eight baby lionfish hiding inside.”

When lionfish spawn, they release two buoyant egg masses every 3 to 5 days, containing between 10,000 to 20,000 eggs in each sack. After they are fertilized, float to the surface. These eggs and later embryos, in their adhesive mucus sacs will sometimes become attached to the floating seaweed, and can float for some 25 to 45 days before hatching out.

He shared his findings with the Joint Nature Conservation Committee at a 2013 Lionfish Response Strategy Workshop on Anguilla. The report noted “Based on observations of juvenile lionfish associated with large plastic debris, and the knowledge that both larvae and eggs are capable of dispersing great distances, the hypothesis that the Sargasso Sea acts as a gigantic nursery ground for lionfish is put forth. Additionally, the preying of juvenile lionfish on the eggs and juveniles of commercially important fish species such as flying fish, dolphin, and tuna, could potentially have a negative impact on the recruitment of these pelagic finfish.

He shared his findings with the Joint Nature Conservation Committee at a 2013 Lionfish Response Strategy Workshop on Anguilla. The report noted “Based on observations of juvenile lionfish associated with large plastic debris, and the knowledge that both larvae and eggs are capable of dispersing great distances, the hypothesis that the Sargasso Sea acts as a gigantic nursery ground for lionfish is put forth. Additionally, the preying of juvenile lionfish on the eggs and juveniles of commercially important fish species such as flying fish, dolphin, and tuna, could potentially have a negative impact on the recruitment of these pelagic finfish.

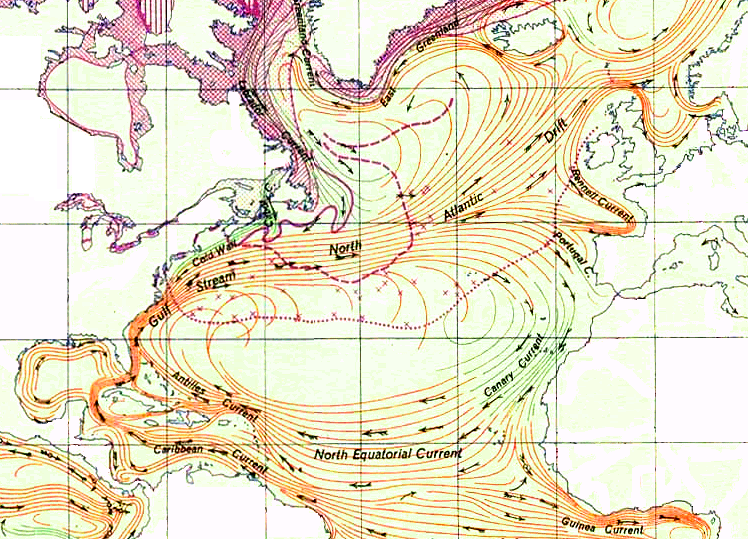

“The nursery role played by the Sargasso Sea and dispersal of this invasive species using the currents of this area is furthermore emphasized by the presence of lionfish on the shores of the Central African Coast, Cape Verde Islands, and Canary Islands, potentially dispersed by the Canary, Equatorial and Guinea Currents surrounding the Sargasso Sea. Research into lionfish larval abundance in the Sargasso Sea and with associated Sargasso weed is needed to identify the role of this area in lionfish reproduction dispersal, should be investigated.”

The diet of the lionfish is varied. In their juvenile life they prey on the eggs and baby pelagics’ of American and European eels, flying fish, mahi mahi, tuna, and even baby sea turtles, says the fisherman. The adults consume over 40 species of fish and crustacean species and is a real threat to many native reef fish populations through direct predation, as well as competition for food resources with native fish species.

Researchers have reported that within a short period after lionfish move into a new area, survival of native reef fishes declines by about 80 percent. Further, the voracious feeding behaviour of these lionfish may impact the abundance of ecologically important species such as parrotfish and other herbivorous fishes that keep sea moss and macro algae from overgrowing corals.

The storms and rough seas help to push the seaweed rafts to break off and be directed down through the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, or across the Atlantic to the Azores; Canary Islands; West Coast of Africa; Central and South America. However, it is the lionfishes laziness and ability to mimic floating seaweed that is helping it to flourish and remain a danger to the region’s fishing sector.

While the spines covering the lionfish are poisonous, the meat is edible and quite delicious. Education campaigns have encouraged the catching and consumption of the fish which is making it an attractive product for fishers.

While the spines covering the lionfish are poisonous, the meat is edible and quite delicious. Education campaigns have encouraged the catching and consumption of the fish which is making it an attractive product for fishers.

Captain Howes is hopeful that organisations like the JNCC and others which continue to look for ways to manage the lionfish invasion will soon prove his hypothesis and lead to new ideas on resolving both the sargassum seaweed and lionfish invasions.

About the Lionfish

- Voracious predators being shown to eat all native fish and crustaceans in large quantities, including both ecologically and economically important species like grunts, snapper, nassau grouper, cleaner shrimp, etc..

- Not known to have any native predators.

- Equipped with venomous dorsal, ventral and anal spines, which deter predators and can cause painful wounds to humans.

- Capable of reproducing year-round with unique reproduction mechanisms not commonly found in native fishes (females can reproduce every 3 to 5 days!).

- Relatively resistant to parasites, giving them another advantage over native species.

- Fast in their growth, able to outgrow native species with whom they compete for food and space.

- Can survive for up to 45 days without eating (making this fish possible to be transported over vast distances, without eating.)

- Can live in waters from 1 foot deep to 900 feet deep.

- Can eat a fish, which is two thirds of it’s size.

- Lionfish usually float around rocks/shoals, appearing to the juvenile fish as a piece of seaweed.

Discover more from Discover Montserrat

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.